Disinformation is the coin of the modern realm. Vaccine denial, climate denial, election denial and war-crime denial have joined the grotesque denial of the Holocaust in the ranks of dishonesties now regularly foisted on the public. We can, however, do something about this crisis of the information age.

In January the World Economic Forum (WEF) ranked the spread of misinformation among the greatest threats to humanity in its Global Risks Report. With more than four billion people voting in the upcoming 2024 elections (roughly half the world’s population), the report makes clear that now is the time to prepare the world against disinformation and those who peddle it.

Some commentators have dismissed the report’s conclusions as another attempt to censor free speech. But this is disingenuous; the people who oppose misinformation research, whether pundits, politicians or crackpots, are not fighting for freedom but against a discerning and well-informed citizenry.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The public’s beliefs, we know, are only partially aligned with the facts: Virtually all Americans, for example, know that Belgium did not invade Germany to start World War I. But one in five young Americans think the Holocaust is a myth. Years after the Iraq War, 42 percent of the public mistakenly believed that weapons of mass destruction had been there. More than one third mistakenly believe that the risks of COVID vaccines outweigh their benefits.

Somebody lied to these people. The difference between justified public beliefs and mistaken ones is usually disinformation, whether spread on social media or through other channels by political actors.

In short order, following the WEF report’s release, pundit Nate Silver declared its nearly 1,500 expert consultants “idiots,” and Elon Musk used the report to decry the very concept of misinformation as an insidious conspiracy. They echoed key talking points increasingly used to downplay the urgency of the misinformation crisis, including the flawed notion that the label “misinformation” is subjective, ambiguous and biased. Philosopher Lee McIntyre has described this effort as the hijacking of postmodern principles to advance a war on truth.

The role of disinformation is particularly apparent with COVID vaccines. Although then President Donald Trump initially claimed credit for their rapid development and deployment, the vaccines rapidly became politically polarized, with Republican politicians and conservative networks routinely seeking to discredit them. One study has linked frequent false statements about COVID vaccines on Fox News to lower vaccination rates among its viewership. Another study found that people who strongly supported Trump were less likely to get vaccinated than others, including Republicans who were not strong Trump supporters. A tragic downstream consequence of COVID disinformation, then, is a widening partisan gap in excess mortality. Mortality rates were equal for Republican and Democratic registered voters prepandemic, but after vaccines had become widely available, excess death rates among Republicans were up to 43 percent greater than among Democratic voters. The gap was greatest in counties with the lowest share of vaccinated people, and it almost disappeared for the most vaccinated counties.

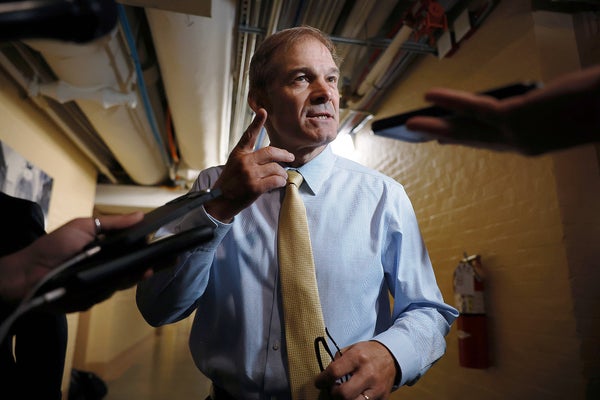

Given that Republicans are the primary victims of vaccine disinformation in the U.S., it is ironic that it would be a Republican, Congressman Jim Jordan of Ohio, who launched a campaign against research that seeks to protect the public from the worst peddlers of disinformation. His campaign is in part based on online conspiracy theories, for example one suggesting that researchers colluded with the Department of Homeland Security to censor 22 million tweets during the 2020 election. In fact, researchers merely collected those tweets for analysis, and flagged about 3,000 of them (about 0.01 percent) for potential violations of Twitter's terms of use. Jordan’s campaign has exerted a chilling effect on the research community, and his attacks have coincided with moves by the major platforms, such as Meta, Google, Twitter and Amazon, to cut back on staff dedicated to combating hate speech and misinformation—not an auspicious move right before four billion people prepare to cast their votes this year.

Jordan’s pursues his campaign under the banner of free speech. Indeed, although there is bipartisan support among the American public to remove false content online when it involves clear cut issues such as Holocaust denial, there are other cases in which it is difficult to label information unambiguously as true or false. But the solution isn’t to sue, harass or censor misinformation researchers.

On the contrary, misinformation researchers have identified novel ways to make people more resistant to being misled without risk of censorship or interfering with anyone’s freedom of speech. One of those techniques is known as “inoculation,” which involves boosting people’s information discernment skills. Key to inoculation or “prebunking” is the realization that misleading or false information has markers that can help differentiate it from high-quality information. The ancient Greeks already knew how to tell good from bad arguments, and 2,000 years later we can be certain that incoherence, cherry-picking or scapegoating are still markers of poor-quality information.

In fact, numerous studies rolled out to millions of people on social media have shown that inoculation in the form of brief informational videos makes people more skilled at identifying manipulation techniques common in misinformation, such as false dilemmas and scapegoating.

Disinformation abounds, and it can kill. Fortunately, it can often be unambiguously identified.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.