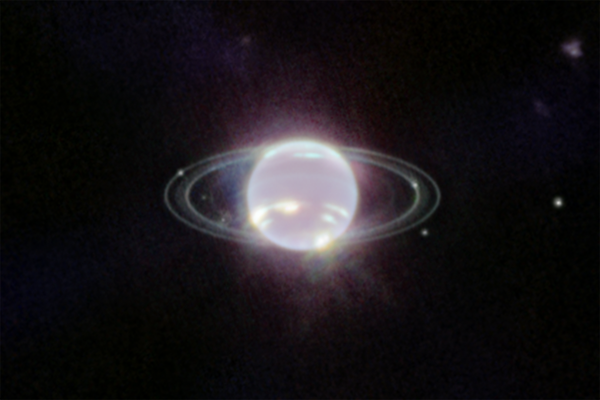

As if dainty, iridescent fairies are racing around a cosmic track, Neptune’s rings sparkle in a stunning new view captured by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the most powerful off-world observatory yet built. This is the sharpest image of the planet’s rings obtained since the Voyager 2 flyby in 1989, and it reveals a plethora of never-before-seen details.

“For me, looking at JWST’s new Neptune image is like catching up with a friend you haven’t seen in ten-plus years—and they look GREAT,” wrote Jane Rigby, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center who serves as the agency’s JWST operations project scientist, in an e-mail to Scientific American.

After a nail-biting launch on Christmas Day in 2021, the telescope began full operation this July and has since splashed the news with jaw-dropping images of nebulae and discoveries of ancient galaxies that could “break cosmology.” But JWST’s keen infrared eyes are opening new vistas closer to home as well when they are turned to our solar system’s retinue of worlds.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

For instance, the telescope’s view of Neptune shows the planet’s tenuous dust bands in unprecedented clarity. These show up as fuzzy particles in between the brighter, ice-dominated rings, says Mark McCaughrean, senior science adviser at the European Space Agency (ESA) and a member of the JWST Science Working Group.

When University of Arizona astronomer Marcia Rieke got a chance to look at the new Neptune views, she says, “as usual, I'm blown away by what we see.” Rieke, who is currently principal investigator of JWST’s main imager, called the Near Infrared Camera (NIRCam), recalls trying to view Neptune’s rings years ago using a ground-based telescope on Kitt Peak in Arizona. “We saw essentially nothing because of how thin and clumpy the rings are,” she says. “It is wonderful to see them so clearly and easily [with JWST].”

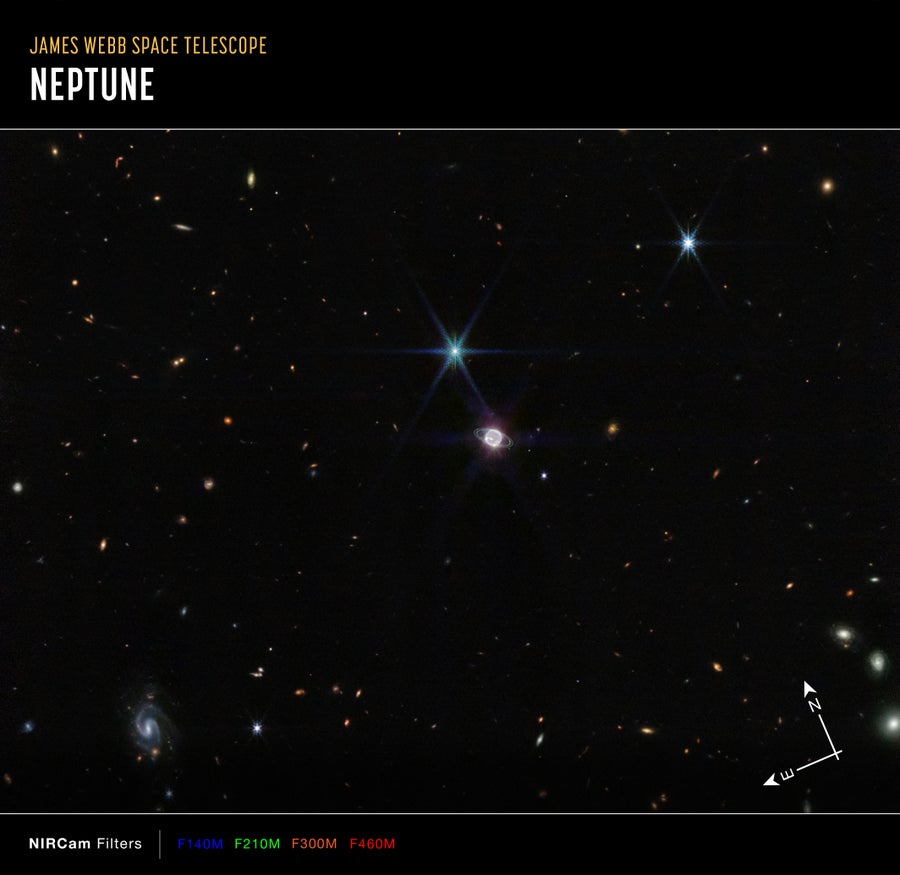

In this image by JWST’s NIRCam, a smattering of hundreds of background galaxies, varying in size and shape, appear alongside the Neptune system. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA and STScI

Clouds of methane ice appear as bright streaks and spots in the image, gleaming in the faint sunlight that reaches Neptune from about 2.8 billion miles away. Seven of the planet’s 14 moons are also tucked into the JWST photograph. The brightest is the oddball Triton, a hefty natural satellite covered in nitrogen ice that reflects about 70 percent of the incoming sunlight. Whereas most planetary moons, including all the others around Neptune, orbit with their planetary host’s rotation, Triton does so in the opposite direction. That orbit suggests to researchers that the body is probably a migrant from the outer solar system captured long ago by Neptune’s gravity.

“That will be really cool to go and measure the spectrum of Triton because it represents a body that came from farther out,” McCaughrean says.

JWST’s infrared view also shows a thin glowing band encircling the equator, likely produced by warmer gas flowing toward Neptune’s midlatitudes as part of an ever churning pattern of global atmospheric circulation. Such features may drive the planet’s powerful winds and storms, according to an ESA press release.

“What really pops out at me are all the gorgeous clouds and storms that are present in Neptune’s atmosphere,” says Nikole Lewis, an associate professor of astronomy at Cornell University. “Neptune has the highest measured wind speeds in the solar system, with average wind speeds near [the] equator of 700 miles per hour and peak wind speeds in places that are more than 1,000 mph.” While Lewis’s own work with JWST will focus on planets beyond the solar system, she calls the new image “an amazing snapshot of its turbulent weather.”

Unlike Voyager 2, which provided snapshots of Neptune from one moment in time, JWST’s studies of Neptune and other denizens of the solar system will continue as long as the observatory itself endures. By comparing these and future JWST images with those from Voyager 2, scientists hope to learn more about longer-term atmospheric changes on the planet, such as Neptune’s seasons, McCaughrean says. Because the planet is tilted at a 28-degree angle along its axis, it experiences four seasons, just like Earth. But on Neptune, each lasts about 40 years as a result of that world’s lengthy 164-Earth-year journey around the sun. This means the planet has just about entered a different season from the time Voyager 2 flew by, McCaughrean says.

While Neptune may be the crown jewel of the newly released snapshot, the zoomed-out view shows “a little bit of the poetic side of the planets hanging in space,” McCaughrean says, referring to the background of far-distant stars and galaxies that seem to surround the ice giant.

At nearly a million miles from Earth and chock-full of imaging tools, JWST will continue to provide deeper and clearer views of the universe and our place in it. “JWST, even in just a couple of months, has already begun to add that cosmic perspective,” McCaughrean says. “But to be honest, you haven’t seen anything yet.”