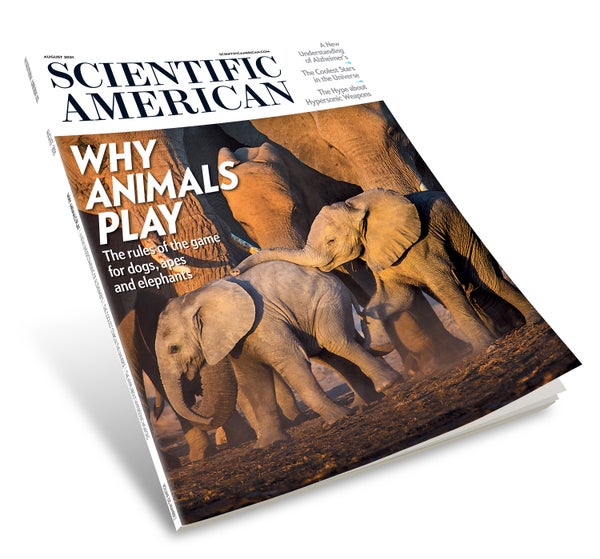

We hope our cover story this month brings you as much joy reading it as we have had producing it. The author, behavioral ecologist Caitlin O’Connell, has what sounds like one of the best jobs on Earth: observing elephants in the wild and making sense of their behaviors. Some of the silliest behaviors turn out to be surprisingly meaningful. Young elephants play in their water holes much like human children play in swimming pools during summer break. They have toys and games and battles, with older relatives ready to intervene if the play turns dangerous. Many social species, from meerkats to dogs to great apes, engage in ritualized play to hone skills they’ll need as adults—and, from everything we can tell, for the joy of it.

Stars and planets are just different ends of a size spectrum, with brown dwarfs in between, astronomer Katelyn Allers explains. They can’t quite sustain fusion like a star does, so they’re harder to see, but they emit enough light from heat that astronomers have recently realized they’re as abundant as stars in the universe, and they’re bizarre. Depending on its age and size, a brown dwarf might have an atmosphere containing titanium oxide or quartz. And Allers has figured out how to measure wind speed on a brown dwarf (2,300 kilometers per hour).

Many of us have lost loved ones to Alzheimer’s and desperately hope for a meaningful treatment. Recent research on immune cells called microglia in the brain is leading to some new approaches. Neurologists Jason Ulrich and David M. Holtzman describe how genetics, mouse models and patient studies point to a two-phase progression of the disease. The story goes into great detail to show exactly where this research stands, with hope but without hype.

As neuroscientist Soo-Eun Chang points out, “speech is one of the most complex motor behaviors we perform.” It’s no wonder there are so many ways it can go wrong. Stuttering is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders, as Scientific American contributing editor Lydia Denworth writes. It affects about 5 percent of children and 1 percent of adults. In the past few years scientists have identified many of the brain regions and some of the genes involved, and they are rolling out new treatments.

It’s refreshing when people who have had a lot of success in their careers recognize the importance of luck. Chemist Jeannette M. Garcia was mixing ingredients in a lab when a reaction went in an unexpected direction and she discovered a new family of polymers. That’s a surprisingly common origin story for many scientific advances, but now Garcia wants to reduce the need for serendipity by using quantum computing to predict the chemically unpredictable.

In our Science Agenda editorial this month, we show that anti-transgender laws are contrary to science as well as cruel. The subject is in the news more than ever these days, but transgender experience is not a fad or an invention. As author Brandy Schillace writes, the first known transgender health clinic was established in 1919 in Berlin. It thrived until it was destroyed by the Nazis and its library consumed by one of the first Nazi book burnings.

In our November 2020 issue, we ran a Graphic Science column revealing that the Southern Hemisphere’s flu season was the mildest ever recorded, an early sign that the 2020–2021 flu season in the North might not be so bad. Data-visualization designer and Scientific American contributing artist Katie Peek follows up with a remarkable series of graphics depicting how flu basically disappeared around the world during the COVID pandemic. The coronavirus is more elusive than flu, in part because it can be spread by those who have no symptoms and don’t know they’re infected. But if people wash their hands, wear masks in crowded indoor areas and stay home if they’re sick, that can stop the flu cold.