Editor’s Note (9/22/2016): This article has been updated from the original to include the location of the hearing and a response from physicians involved in a stem cell treatment study.

Earlier this month the U.S. Food and Drug Administration opened its doors to public commentary on its newest guidelines on the use of therapies derived from human tissues, including stem cells.

The new guidelines, drafted last October, clarify existing regulations by outlining what uses of human tissue can be offered to patients without FDA approval. Many clinics offer patients unregulated, experimental procedures that have not yet undergone the official FDA approval process, which can take years. The major points in the new guidelines specify that: the function of these cells in the recipient’s body must be the same as in the donor; the treatment cells don’t affect the whole body of the recipient; and manufacturers can only manipulate the cells “minimally.” They also state which chemicals manufacturers can use to treat cells and prevent disease transmission.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The FDA notes the revised guidelines are meant to help manufacturers navigate regulations that are already in place. But many interpret them as a crackdown on clinics offering patients experimental procedures. “It is possible that after these public meetings the FDA may step up its activities on clinics to a more proportionate level and send a signal that it is indeed going to rein in the dangerous stem cell clinic industry for real,” says Paul Knoepfler, a professor of cell biology at the University of California, Davis, who specializes in stem cells.

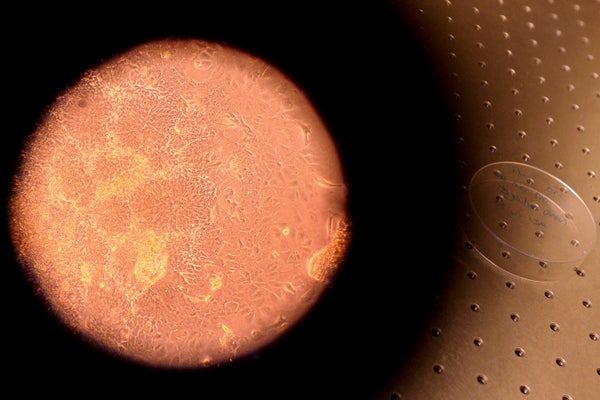

Although preliminary evidence for stem cell therapy for a variety of conditions has been promising, its safety and efficacy are still unproved. There have been few clinical trials—they are expensive and take years. The result is that experts still don’t know important details like dosing and best clinical practices for stem cell treatments.

Some believe such restrictions will help keep desperate patients safe from untested—and sometimes dangerous—procedures. Critics, on the other hand, say that tighter regulations could deny those same patients a viable treatment for debilitating illnesses.

Not all procedures come with equal risk. Clinics offering treatments of using stem cells derived from human fat are the most common, and questionable, procedures. These critics have been among the most vocal opponents of FDA interference. But the new guidelines may also restrict procedures that are generally considered safe. For example, if the guidelines move forward as they are now, fat grafts may no longer be usable for breast reconstruction, and it may be harder for clinicians to get their hands on amniotic membranes that can help wounds heal.

Feedback on guidelines like these is usually confined to written commentary, or to a one-day hearing. But because so many parties were interested, this month's hearing—held in Bethesda, Maryland, on the NIH campus—was double that length; and over those two days, nearly 90 clinicians, patients, biotech companies and scientists offered short testimonials about their expertise or experience. That interest speaks to the gravity of the issue, Knoepfler says.

A number of patients spoke on the second day of the hearing, reporting recoveries due to stem cell therapy that they described as “amazing” and “remarkable.” They implored the FDA to loosen restrictions to give patients access to these procedures. “These are my own cells, and I respectfully ask that you treat them that way,” said Georgianna Crocker, a patient from Austin, Texas. Her rheumatoid arthritis is now in remission.

But not every story of stem cell therapy has such a rosy outcome. George Gibson was in his late 60s when he partially lost his vision during heart surgery. He says he paid $20,000 to get stem cells injected into his eye with the guarantee that he would be able to read a few more lines on an eye chart. Gibson claims that instead, he lost vision in that eye completely, but his assertions could not be verified. There have been other reports of vision loss in stem cell procedures peformed elsewhere. Gibson didn’t get one of the first-come-first-serve slots to speak at the hearing; instead, he and his wife stood outside the meeting room during breaks with big signs that read, “I lost my sight to the SCOTS stem cell procedure!!!”

SCOTS (Stem Cell Ophthalmology Treatment Study) is an Institutional Review Board (IRB)-approved clinical study registered with the National Institutes of Health. The study’s goal is to evaluate the use of stem cells for the treatment of retinal and optic nerve damage or disease. “We would like to clearly state that all patients who enter SCOTS receive a thorough ophthalmic eye exam and complete informed consent prior to any treatment—approved by our IRB—listing risks and potential complications, and that predicting whether there will be visual improvement from the procedure is not possible,” Dr. Steven Levy, the study’s director, said in a statement. "Dr. Jeffrey Weiss [the study’s principal investigator] specifically and unequivocally explains that no guarantees about outcomes of the procedure can be made."

Indeed, several doctors, researchers and nurses who spoke at the hearings said that patients are the ones who suffer in an unregulated system. Leigh Turner, a professor of bioethics at the University of Minnesota, said in the hearing that some companies make "unsubstantiated claims" about stem cell treatments and continue to profit off patients that fall for them. “Some [clinics] falsely claim their studies are ‘NIH or FDA approved,’” which journalists later find to be false, he added. Turner, along with many others at the hearing, encouraged the FDA to increase its oversight to better protect patients.

In the other camp, clinicians and industry representatives pushed back on the FDA’s restrictive wording in the guidelines, likely to preserve their business model, Knoepfler says. Many asked to tweak definitions of specific wording in the guidelines, such as the meanings of “homologous use” (tissues that must have the same function in the recipient as they did in the donor) and what it means for cells to be only “minimally manipulated.” Some told the FDA to scrap its draft completely whereas others commended the agency on its more restrictive wording with only minor edits. There were suggestions for making the industry more transparent with a database of clinics, doctors, patients and adverse effects, like those that exist for other types of tissue transplants. “The draft guidances make sense to me as a stem cell biologist,” Knoepfler says. “They may need some fine tuning over the years, but they largely get things right.”

None of the FDA officials offered any reaction to the comments made at the hearing nor have they set a deadline by which they will issue final versions of the guidelines. The comment period for the draft guidance will close on September 27 and FDA officials encouraged interested parties to submit their feedback in writing.