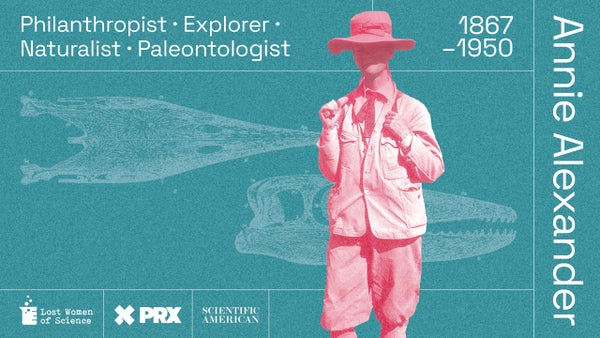

Annie Montague Alexander was an adventurer, an amateur paleontologist and founding benefactor of two venerated museums at the University of California, Berkeley: the University of California Museum of Paleontology and the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology. Born in 1867, she was the daughter of a wealthy sugar baron, but she never quite fit in with her high-society peers. Instead Alexander created for herself a grand life out of doors, away from the constraints of the era: she funded and took part in expeditions to hunt fossils up and down the West Coast. And sometimes she wore pants!

But there was a catch. Alexander always had to be accompanied by a female chaperone because it was considered unseemly for a woman to travel surrounded only by men. Luckily, this worked out well for Alexander: one of those female chaperones would become her life partner.

LISTEN TO THE PODCAST

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

[New to this season of Lost Women of Science? Listen to the most recent episodes on Emma Unson Rotor, Mária Telkes, Flemmie Kittrell, Rebecca Lee Crumpler and Eunice Newton Foote.]

Lost Women of Science is produced for the ear. Where possible, we recommend listening to the audio for the most accurate representation of what was said.

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Katie Hafner: In the spring of 1905, Annie Montague Alexander set off on an expedition to the West Humboldt Mountains in Nevada, in search of fossils. The area was rich in Triassic era bones—and for two months, she and a small team of paleontologists and field assistants went to see what they could dig up.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Women didn’t usually get to go on trips like this, but Annie came from a wealthy family, and she actually financed the expedition. And she was thrilled to be there. She was doing paleontology! Out in the field. She couldn’t ask for more.

But in the collection of photos from the trip, there’s one picture that stands out, a picture of two women at a table washing dishes. It’s Annie and the only other woman on the trip, Edna Wemple. They cooked, they cleaned up. Annie wrote about it in her scrapbook. Katie, will you do the honors?

Katie Hafner: I would be honored to do the honors.

Katie Hafner as Annie Alexander: “My dear friend Miss Wemple stood by me through thick and thin. Together we sat in the dust and sun, marking and wrapping bone. Night after night, we stood before a hot fire to stir rice, or beans, or corn, or soup, contriving the best dinners we could out of our dwindling supply of provisions. We sometimes wondered if the men thought the firewood dropped out of the sky or whether a fairy godmother brought it to our door, for they never asked any questions.” [quote slightly abridged]

Carol Sutton Lewis: Of course they didn’t. The men didn’t seem to have much interest in the mundane tasks of maintaining a campsite. So even though Annie and Edna were doing fieldwork alongside the men, and Annie had even paid for the trip, she and Edna became the de facto cooks. Don’t worry. It gets a lot better.

Katie Hafner: I’m Katie Hafner.

Carol Sutton Lewis: And I’m Carol Sutton Lewis.

Katie Hafner: Today we tell the story of Annie Montague Alexander, whose passion for paleontology— along with her money—led to the creation of two of the world's most venerated research collections.

Carol Sutton Lewis: UCBerkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, or MVZ, as it’s called on campus, is not your typical natural history museum. There aren’t any dioramas or animals in fierce poses on display, although at the base of the staircase leading to the museum, there’s a complete T-Rex skeleton that’s sometimes dressed in a Santa hat around the holidays. The MVZ is strictly for research. Closed to the public. But a few months ago, our producer, Alexa Lim, got a private tour.

Michelle Koo: Hello [off mic].

Alexa Lim: Oh hey, how are you?

Michelle Koo: [inaudible]

Alexa Lim: I am. I got distracted by the dinosaur.

Michelle Koo: Yup, totally understandable.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Michelle Koo is one of the curators in charge of the collection. There are more than 700,000 individual specimens here – fish, bears, birds, you name it.

Katie Hafner: Annie founded this museum in 1908, and she herself trapped and prepped many of the animals in its collection.

Michelle Koo: So just to give you an overview so you can see she's collected over 6,000 specimens, and that's a lot for a single person, (laughs) over the course of their career.

Katie Hafner: And a lot of these specimens were gophers. To find them, Alexa and Michelle wind their way through a series of rooms with hundreds of cabinets and shelves.

Michelle Koo: Walking through the bird collection right now. So all-

Katie Hafner: Michelle turns a latch on a towering metal case that they pass. She pulls out a wooden tray.

Michelle Koo: So this is a tray of hummingbirds.

Katie Hafner: Then, they reach the rodents.

Michelle Koo: I think the rodents are all over here. I think we went too far when we went through the squirrels.

Katie Hafner: And at last, they find the gopher section. Michelle starts sorting through the trays.

Alexa Lim: Looks like a bunch of little hot dog buns.

Michelle Koo: Yeah, they do look like hot dog buns.

Unnamed speaker: Let’s just go real quick and-

Michelle Koo: Oh Annie! Oh, there we go! Thomomys bottae pervagus from New Mexico. We found the little hot dog buns.

Katie Hafner: And next to each one is a little label with the species, date of collection…and Annie’s name. So it takes some digging before you find her name on anything in this museum.

But none of this would be here— the birds, the building, the hot dog buns - without Annie—without her hard work, and her money.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Annie Alexander was born in 1867 in Honolulu, the second of five children. She spent her early years in Maui where her father, Samuel Alexander, and his business partner started their first sugarcane plantation on over 500 acres of land.

Their company, Alexander and Baldwin Incorporated, would eventually become one of the biggest sugar companies on the islands. And we have to note that the history of the sugar industry in Hawaii…isn’t pretty. White plantation owners amassed wide swaths of land at the expense of indigenous Hawaiians, and brought in a largely immigrant workforce who toiled in poor living conditions and were sometimes severely punished for minor transgressions.

We tried to find out what exactly Alexander and Baldwin’s practices were. And we had some trouble at first. But then our fact checker, Lexi Atiya, found this old report in a sugar trade association’s newsletter. It was all about immigration. Plantation owners needed a big immigrant workforce to support their industry. And this report is blatantly racist. The writers talk about which races are best suited for this kind of labor, which ones are quote “imbeciles”, and which ones are too smart and might organize to stop them from lowering wages. They also write about how to get rid of immigrants who are no longer useful to them.

The first author of this report is Samuel Alexander.

Katie Hafner: But we don’t know what Annie would have seen or heard about her father’s business while she was growing up. What we do know for sure is that Annie grew up with a lot of money…and a lot of freedom.

Now, most girls of Annie’s social and economic class were expected to attend afternoon teas, learn needlepoint, and eventually, find a husband and raise a family. But Annie wasn’t interested in any of that. She was more interested in a life outside. Swimming in the ocean, climbing the roof of their house.

Barbara Stein: She really lived a life out of doors. I mean, nature was outside her bedroom window.

Katie Hafner: Barbara Stein is the author of On Her Own Terms, a biography of Annie Alexander. And she also worked at Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology as a researcher and curatorial associate for more than 15 years.

Barbara Stein: She really had difficulty conforming to societal strictures. She was not interested in most of the things that women at that time were engaged in.

Katie Hafner: And she had her father’s blessing. He’d take her camping, teach her how to shoot guns.

Barbara Stein: Samuel was a very unusual man of the time because he encouraged things in Annie that most fathers would not have encouraged in their daughters at that time.

Carol Sutton Lewis: But when she was a teenager, Annie’s life ‘out of doors’, as she called it, came to an abrupt end. In 1882, Samuel moved the family from the tropical climate of the island to the busy streets of Oakland, California.

Upscale city life was a whole new world for Annie—the fashionable department stores, the trolley cars, society life—and she didn’t like it. She hated the afternoon teas, where she wrote she felt like a masquerader amongst the masked.

And for a while, it seems like Annie was a bit lost. In her 20s, she attended a women’s college on the East Coast, studying things like French, civics, and photography. She left without graduating. Back in Oakland, she dabbled in art. Nothing took.

Katie Hafner: But in the fall of 1900, when Annie was 32 years old, a good friend encouraged her to audit some classes at Berkeley. She started with paleontology. It was a class taught by John C. Merriam, who specialized in vertebrate fossils of the West Coast. He was known to be a passionate and inspiring lecturer. Annie was captivated. Paleontology allowed her to imagine the distant past, a time when the coastal lowlands were tectonically squeezed into the Oakland hills of today. And a time when the ancestors of camels and elephants roamed in a prehistoric California.

For someone like Annie, who was intellectually driven and who craved a life of adventure outside, paleontology was perfect. She wanted to learn as much as she could and to get her hands dirty; to go out in the field herself.

And that was a problem. Back then, women who were interested in the natural world, even very wealthy women, maybe even particularly very wealthy women, were often pushed to pursue gardening or writing, maybe to study botany, which was seen as relatively feminine. They might even become illustrators for their scientist husbands.

But Annie had free use of her family’s sugar money and she wasn’t about to stand on the sidelines. Within a year of signing up to audit these paleontology classes, she went from student to patron of the sciences. She was actually funding her professor’s expeditions, and in the spring of that year, he helped her organize her own. The destination: Fossil Lake in Oregon.

Carol Sutton Lewis: The planning was exhaustive. Annie and her team had to plan out transportation, food, shelter, everything they’d need to fend for themselves for an 11-week trip in turn of the century America.

Barbara Stein: There was no Gore Tex back then and no nylon and polypropylene.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Barbara Stein again.

Barbara Stein: I mean, we're talking big, heavy canvas tents, you know, that would get soaked in the rain. You're lugging heavy traps. You're lugging guns and ammunition, not only to protect yourself, but also on many of these expeditions, like Fossil Lake in order to procure enough fresh food because you are out in the middle of nowhere, pretty much for a couple of months. And so you can bring your corn meal and your sugar and beans, but you wanna supplement that with the occasional rabbit or partridge or whatever you can catch. It was pretty rigorous.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Annie and her team prepared everything. But before they could leave, there was one last item on the checklist: Annie had to secure a female traveling companion.

Barbara Stein: Women did not go out in the field by themselves. There had to be at least one other woman with them for the sake of propriety. Because men would be talked about. She would be talked about. And that gossip alone could undo a field party.

Carol Sutton Lewis: So even though she was funding the entire trip, she would still need to find a chaperone. She ended up asking an acquaintance, Mary Wilson, who was a teacher in the city. Mary didn’t have any field experience, but Annie wrote to a friend that she thought Mary was strong and self-reliant. And in May, the team set off.

Despite all of the planning, they ran into obstacles. It took nearly a month just to get to Fossil Lake. They’d walk for hours a day at times, and it was often freezing cold at night. At one point, they had to steal fence posts to use as firewood.

But Annie felt at home, and the trip was a success. The team returned with 300 pounds of fossils. Mostly horses, camels, and birds. Annie herself collected more than 100 bones.

And this expedition clarified her sense of purpose.

Barbara Stein: Alexander believed that the happiness she experienced in the field really had to be earned. It gave her an opportunity to camp, to explore, and by donating these fossils, to feel that she was being useful, that she would be contributing to our understanding of the evolution of life and of the natural world.

Katie Hafner: Annie still wasn’t officially enrolled in the university as a student, but she had proven herself to be a skillful field worker. Fossil Lake would be the first of many trips to come.

Barbara Stein: She had a good eye. She could identify potentially valuable outcrops. When she started trapping mammals, she had a good sense of where to set those traps. She was highly regarded for her expertise as a field biologist.

Carol Sutton Lewis: But Annie never became a professional scientist. She never published any papers herself. Despite all of her accomplishments, she might not have felt capable of it. In letters to her friend Martha, she confessed self-doubt.

Katie Hafner as Annie: “I stand aghast when I am brought face-to-face with what a real student accomplishes—what a trained mind with a large brain can do—and I feel perfectly hopeless.”

Carol Sutton Lewis: But Barbara thinks there was another reason Annie didn’t pursue a career in science: her money.

Barbara Stein: The best interpretation that I can put on that, is that she recognized she could probably contribute more through her financial donations and her specimen contributions and her business acumen.

Katie Hafner: Her money gave her the kind of power most women—and most scientists—just didn’t have. In the fall of 1907, she wrote a pretty bold letter to the University of California president Benjamin Wheeler: “Dear President Wheeler, Should the University of California within the next six months erect a galvanized iron building furnished with electric light, heat and janitor services and turn it over to my entire control as a Museum of Natural History for the next seven years, I will guarantee the expenditure of $7000 yearly.”

I love that. Should! Should the University of California. Just in case the universe should happen to erect. Anyway, this museum would be dedicated to the mammals, birds, and reptiles of the West Coast, a museum of vertebrate zoology, a.k.a the MVZ. Annie was giving the museum enough to cover supplies and equipment, staff salaries, and then some. And the university would own the museum. But Annie would completely control the research program and how the museum spent her money. Basically, this letter is your classic, you’ll get my money, but I call the shots.

I have to stop here for just a second. Carol, you're there, right? (mm-hmm) Okay. So when we were first thinking about doing the Annie Alexander episode all the way back, like, three years ago, there was a senior producer with us then who was very, um, how should we put it, uh, skeptical about devoting an entire episode to someone who she said bought her way into the science. And can someone, you know, use their money to buy themselves something? Yes, yes, yes. But Annie, let's think about this. She had a skill and a passion.

Carol Sutton Lewis: And look, she had money, but unlike other people in her era, she chose to use the money she had to pursue not just her passion, but to make these scientific discoveries available to the world through museums. So, you know, I think with this episode, we're rightfully expanding the definition of, who can be heralded in the world of science to include people who made it possible.

Katie Hafner: I know that Elah, our current senior producer, is eavesdropping on this. Elah, do you have an opinion? Hi Elah.

Elah Feder: Oh hi. Do I have an o-? I- I was skeptical too. I wouldn't say she bought her way in. And also, at the time, women couldn't access scientific careers as easily, so if you're part of a group that's discriminated against, and that's the reason that you're denied access, you know, paying to enter isn't necessarily the worst thing in the world. But, I did think that our focus was on women who either discovered something or invented something. And I thought those stories were the most interesting. And, it's not-- the stories of how someone financed something don't inherently call out to me. (laughter)

What won me over, and I don't want to give too much away because this episode is not over and there's some good stuff coming, but what won me over was, that she did go on these really cool expeditions herself, and then, I think is important to talk about the role of money in science. So, you know, I don't, think what she did was ignoble. Money in science, it is essential. But I don't know that I, I mean, when you, what you just heard is a person who used her money, not just to be a philanthropist and allow science to happen and flourish, but to control it. And I don't know if she is inherently, by virtue of having money, the best positioned to control it.

Katie Hafner: Here’s the real question as I see it. Was her goal to get her name up there? Her goal was to amass this collection and make it available to researchers, so I see that as a noble, worthy goal, and also, what a character, which we’re going to see more of. And let’s keep going.

Carol Sutton Lewis: [laughs] As much as we’ve been focused on Annie getting to call the shots, this wasn’t just a vanity project for Annie.

Katie Hafner: Right, a big part of this museum was about documenting the fauna of the West Coast—while it was still there.

In the mid-1800s, when gold was discovered north and east of San Francisco, California’s population boomed. And it kept on growing into the next century. All that development meant digging up the landscape, deforestation, and endangering the species that lived there.

Barbara Stein: I think she actually was aware that the fauna of the West Coast was rapidly disappearing. And if a collection wasn't made soon or at least started, that fauna would disappear forever, and there would be no document of what the state looked like. And her recognition of that I think was truly remarkable because there weren't a lot of other people in the country at the time who were aware of that, and even fewer who were willing or had the means to act on it and do something about it.

Katie Hafner: The university accepted Annie’s proposal. And 1908 was going to be a very big year for Annie. She got her museum of vertebrate zoology. And she was also about to meet Louise Kellogg. You know how to keep things extra proper she always needed to have a female companion? Well, Louise was going to be her final female companion, her female companion for life. After the break.

===== BREAK =====

Katie Hafner: In 1908, everything seemed to be turning up Annie. The Museum of Vertebrate Zoology opened on the Berkeley campus that year. Newspapers wrote about the museum and the brave explorers contributing to its collection. Even President Theodore Roosevelt donated specimens from his famous hunting trip in Africa. An article in the San Francisco Call and Post said it was all thanks Annie Alexander’s generous financial donation, but that her modesty was such she didn’t want her name to be associated with the museum. At least, that’s what she told the newspaper.

Carol Sutton Lewis: But even if her name wasn’t on it, this was Annie’s museum. Everything was under her control. She even hand-picked the museum’s first director.

Barbara Stein: That was a sticking point for the university and the regents.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Barbara Stein again.

Barbara Stein: I mean, they were not used to having a patron dictate who would be on staff. And so she finessed that.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Annie’s choice for director was an interesting one: Joseph Grinnell. Outside of biology, most people don’t know his name, but he’s the guy who came up with ecological niches. So he knew his stuff. But he didn’t seem to have much respect for women. Under his tenure, no women were allowed on expeditions the museum sponsored. And Annie let him get away with that. I can only assume she was used to compromising, and to the limitations of men in her era.

And what mattered to her was that she and the museum’s director saw eye to eye. And from their first meeting, she was impressed with Joseph.

Barbara Stein: They were immediately on the same wavelength. Grinnell was keeping up on the literature of the day, and he actually found a publication, which acknowledged her contributions and that sort of gave her even more credibility in his eyes. Neither of them suffered fools lightly, and had he just been paying lip service, she would have recognized that right away and not tolerated it. Neither of them had any interest in fawning behavior, if you will.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Whatever his opinions were on women, it seems he decided Annie was the exception and he genuinely respected her for her intellect and adventurous spirit.

Katie Hafner: So Annie’s vertebrate museum opened with Joseph Grinnell as the director and started filling up with specimens. And that same year, 1908, Annie went on another big expedition. This time, to Alaska. And once again, she needed a traveling companion. She asked Joseph if he had any recommendations. He told her he couldn’t think of any. The women he knew were parlor botanists or at most opera-glass observers, whatever that means. No, he couldn’t think of a single woman who had what it took for that kind of expedition.

In her letter back to Joseph, Annie was clearly annoyed. She told him she regretted his quote, evident contempt of women as naturalists. But never mind, just a week later, she wrote again saying she’d found someone. Her name was Louise Kellogg.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Louise was no paleontologist. She’d studied classics at Berkeley, and when Annie met her, she was teaching primary school. But her dad had taught her how to hunt and fish, useful skills on an expedition, and Annie took a shine to her, and off they went.

It was a miserable trip in a lot of ways. When it wasn’t pouring rain, they were getting devoured by insects. And they weren’t finding the diversity of wildlife they’d hoped to. At first, they collected mostly rodents and birds. And later on, they killed two bears. But this trip was one of the most important in Annie’s life because of Louise. After Louise left the expedition, Annie wrote to her good friend, Martha Beckwith: “The greatest discovery of this trip was Louise. Surely I was fortunate but the more forlorn now to be left alone with the lapping of the waves on the beach and the rain on my tent roof.”

Katie Hafner: It wasn’t long before Annie and Louise completely merged their lives. Early on, Louise quit her job as a school teacher, and took up the life of an adventuring paleontologist. Unlike Annie, she even authored some papers. In 1910, so just two years after that rain-soaked Alaska trip, Louise published a paper on rodent fossils in Nevada making her either the first or second woman ever to publish on mammology—we’ve seen mixed reports but either way, well done, Louise!

A year after that, they moved in together. Annie bought them a plot to live on—more than 500 acres on Grizzly Island, near Sacramento where they grew asparagus. Their asparagus became famous statewide.

Barbara Stein: Prior to asparagus, they were well-recognized for the milking Shorthorn cattle that they bred. I mean, whatever she did, she really set out to learn about it and do it in the best possible way.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Farming life complemented their travels. They took advantage of the off-season to go on more expeditions over the years—to the Mojave Desert, the Eastern Sierra, mostly the Southwest, though they also made it to Annie’s beloved Hawaii.

And under Joseph Grinnell’s direction, Annie’s museum was still doing well, so in the spring of 1921, Annie decided, what the hell, let’s start another museum at the university. Her first one had been dedicated to living species. This one would be for extinct ones, a museum of paleontology. Once again she wrote a letter to the university, offering funds and listing a bunch of stipulations. And this time, they were quick to agree. They’d seen how successful her first museum was. So within a few months, the University of California Museum of Paleontology was created.

It’s actually in the same building as the MVZ. Remember the dinosaur that wears the Santa’s hat at the building’s entrance? Well, he belongs to the Museum of Paleontology.

Katie Hafner: So life was good for Annie and Louise. They had their sprawling asparagus farm and a life of adventure out of doors. As to the exact nature of their relationship, they never said it was more than a close friendship, so we can only speculate.

Barbara Stein: They were collecting partners and I think they were long-term lovers. There was a 13-year age difference between them. But, um, Louise also grew up in, in an affluent family in Oakland. She never married. And once they met in 1908, they spent the rest of their lives together.

Katie Hafner: In the early 20th century, their relationship wouldn’t have been recognized.

Barbara Stein: I think her lifestyle was unusual enough that she also didn't want to be the subject of gossip or draw attention to herself in that way.

Katie Hafner: How do you avoid society gossip? Avoid society.

Barbara Stein: When they weren't in the field, they spent most of their time on the farm. And so they just avoided, they did have an apartment in Oakland for a number of years near Lake Merritt, but, um, they just avoided society largely. And I think if you have money, money can insulate you.

Katie Hafner: Annie and Louise spent the rest of their lives together – 42 years in all. And their lives were just about as intertwined as they could be. They even shared a diary, and one of them wrote in it every day. Until the fall of 1949 when the pages go blank.

In early November of that year, Annie hadn’t been feeling well. Louise thought it was serious, but Annie insisted she could recover at home, as long as Louise cooked her some nutritious food. It didn’t work. Annie’s condition deteriorated, and soon, she went to the hospital. Two days later on November 11th, 1949, she suffered a major stroke and fell into a coma.

Louise kept writing in their diary at first, noting all of Annie’s visitors, the cards and gifts people sent. She was still hopeful Annie would recover. But ten months later, on September 10th, 1950, Annie died. And Louise added a final entry. Just one word: Finis.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Both of Annie’s museums still stand today. And her Museum of Vertebrate Zoology -or zoology as the experts say- is one of the top 10 vertebrate collections in the world, used by scientists for research worldwide.

On the day Alexa visited, Michelle Koo took her to her favorite room - the amphibians and reptiles.

Michelle Koo: Sothis is what we call the wet collection. So you can see these rooms are like specially built for these kinds of collections. It feels a little cool in here. We've got these metal, um, bolted on shelves. Each shelf has earthquake straps. If there was a catastrophic, you know, uh, situation where every jar broke, we do also have these special floor drains,

Alexa Lim: Oh, wow.

Michelle Koo: So they can't. You know…

Alexa Lim: escape.

Michelle Koo: Yes. Can't escape.

Carol Sutton Lewis: She pulls out a jar that Alexa tells us is best described as a frog snowglobe. A jar full of three-inch long frogs bobbing up and down in a clear liquid. These are Mountain Yellow-Legged Frogs, a species Michelle has studied herself. And one that Joseph Grinnell collected in the fields surrounding Berkeley 100 years ago.

Michelle Koo: I'm reading his field notes or his colleagues' field notes, and they were saying they couldn't walk without stepping on frogs. Whereas when I went back to the same meadows, we were finding zero frogs.

Carol Sutton Lewis: It’s not just these frogs. Back in the 1980s, scientists realized that frogs worldwide were disappearing, being wiped out by something called a chytrid [KITRID] fungus that attacks frog skin. Infected frogs start to lose weight, their skin starts to slough off, and sometimes, they die.

Katie Hafner: Without notes like Grinnell’s, and without the museum’s collection, modern scientists might not have even known that species like the Mountain Yellow-Legged Frogs even existed in the area. The museum lends out skins, skeletons and some specimens to researchers, kind of like checking out a book from a library.Researchers might clip a fur sample to analyze toxicity levels in a species over time. Or examine a species of bird to see how its range has changed in the last century. All of this data is contained within the drawers of the MVZ.

Michelle Koo: Our main responsibility is basically to be a biodiversity archive. If we know where species or a specific specimen is actually from, then we have like this ecological snapshot for that species at that time and place. And that might tell us all sorts of other things.

Carol Sutton Lewis: And it all started with work that Annie did and funded; the work of trekking out into nature, documenting what’s there over and over to see how ecosystems are changing, to see what’s new, what’s gone extinct, and what’s slipping away. The work won’t save the frogs on its own, but knowing what’s happening is the first step. And as Annie wrote back in 1911-

Katie Hafner as Annie Alexander: “I sometimes feel that one’s efforts to advance science by this sort of work are so feeble that it is almost ridiculous, but I suppose we must do the best we can, and leave to future generations with bigger brains what is beyond us to master.”

Katie Hafner: This episode of Lost Women of Science was hosted by me, Katie Hafner.

Carol Sutton Lewis: And me, Carol Sutton Lewis. It was written and produced by Alexa Lim with senior producer, Elah Feder. Lizzie Younan composes all of our music. Paula Mangin creates our art [Art for this episode was designed by Keren Mevorach]. Samia Bouzid sound designed and mastered this episode.

Katie Hafner: We want to thank Michelle Nijhuis for her early reporting, as well as Mark Goodwin for turning us on to Annie in the first place. Thanks Jeff Delviscio at our publishing partner, Scientific American, and executive producer Amy Scharf, as well as senior managing producer, Deborah Unger.

Carol Sutton Lewis: Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Anne Wojcicki Foundation. We're distributed by PRX.

Katie Hafner: See you next week.

-------------------------

For show notes and transcript, visit lostwomenofscience.org

Hosts: Katie Hafner, Carol Sutton Lewis

Producers: Alexa Lim (producer), Elah Feder (senior producer), Michelle Nijhuis (contributed early reporting)

Guests: Michelle Koo is a staff curator at the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology at UC Berkeley.

Barbara Stein is the author of On Her Own Terms, a biography of Annie Alexander.

Further reading:

On Her Own Terms: Annie Montague Alexander and the Rise of Science in the American West, Barbara R. Stein, University of California Press, 2001.

Annie Alexander profile, UC Museum of Paleontology website.

The Annie Montague Alexander Papers, archives of the University of California Museum of Paleontology.

Louise Kellogg profile, Museum of Vertebrate Zoology website.