For the first time, scientists have unearthed direct proof of what a tyrannosaur—often thought of as the epitome of fearsome predators—actually ate.

The fossilized stomach contents of one member of this dinosaur family were described in a new study published on Friday in Science Advances. This remarkable discovery gives insights into the tyrannosaur diet and the animal’s place in ancient ecosystems, both of which have previously only been hypothesized about.

Darren Tanke, a fossil preparator at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Alberta, found the specimen in the province’s Dinosaur Provincial Park and delicately removed it from the rock in which it was encased. He called it “the discovery of his life,” according to study co-author François Therrien, the museum’s curator of dinosaur palaeoecology.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The study examines remnants of two small oviraptorosaur—feathered dinosaurs with a toothless beak—that were found in the stomach of a young Gorgosaurus libratus, a type of tyrannosaurid. (The family includes this species’ more famous cousin Tyrannosaurus rex.) Before the new fossil find, scientists could only infer anything about the tyrannosaur diet. Such inferences have been based on things like fossils’ skull and tooth structure, bite marks on megaherbivores’ fossils and at least one coprolite, or fossilized feces. Bones found near one tyrannosaur fossil have also been interpreted as stomach contents. The circumstances that can lead to the fossil preservation of stomach contents are unusual: an animal would need to die before the complete digestion of prey and then be rapidly buried by mud or another medium.

“Direct evidence of diet in dinosaurs is frustratingly rare,” says Lindsay Zanno, head of paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and an associate research professor at North Carolina State University, who was not involved in the new research.

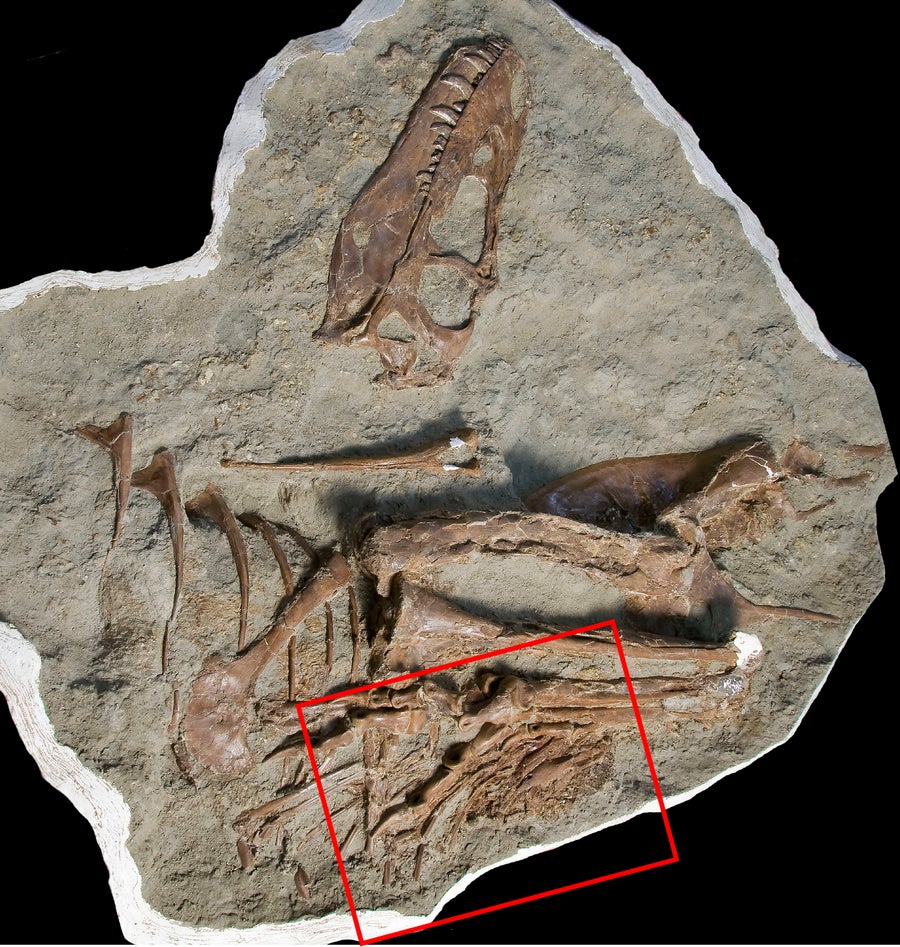

Gorgosaurus skeleton left view showing location of stomach contents. Credit: Copyrights Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology

Gorgosaurus lived in the late Cretaceous period, approximately 80 million to 66 million years ago. Leggy and slender with bladelike teeth in its youth, it developed into a massive apex predator as an adult, almost twice the height of a giraffe and weighing as much as an elephant. That transformation made paleontologists think the animal underwent a significant dietary shift during its lifetime. A young Gorgosaurus wouldn’t be expected to attack the megaherbivores it could tackle as an adult; smaller prey would make more sense.

Bone growth analysis revealed that this tyrannosaur was a juvenile between five to seven years old and that both of its prey had lived for less than a year. The differing amount of stomach acid etching on the prey remnants indicates the animals may have been consumed within hours or days as separate meals. And the fact that the remnants included fully articulated legs from two oviraptorosaurs of the same age, size and species suggests the animals were a favored menu item of this particular tyrannosaur.

The oviraptorosaur legs enabled the team to identify the prey as Citipes elegans—specimens that were “extremely rare” in terms of their relatively pristine condition. “Ironically, the tyrannosaur stomach actually protected the Citipes, enabling it to be preserved—which is quite neat,” says study co-author Darla Zelenitsky, an associate professor at the University of Calgary. These Citipes fossils are, she adds, “the most complete remains known for that species.”

Gorgosaurus probably “dismembered the small prey, swallowed the legs and left the rest of the body out there,” Therrien says. He suggests these legs may have been “the meatiest part” of the animal and wonders, with a laugh, if perhaps this Gorgosaurus “didn’t want to be bothered having to cough up some feathers.”

“With the discovery of this remarkable specimen, we have direct, irrefutable evidence of not only what this species was snacking on,” Zanno says, “but the gory details of how it went about it.”

Oviraptorosaur nests typically contained at least 30 or more eggs. With such large broods, “you could imagine, at certain times of year, depending upon the species and when their breeding season is, this would not be an uncommon prey for predators,” Zelenitsky says. That’s why she isn’t surprised to find remains of this species in this Gorgosaurus’ stomach, especially because she “can’t see the adults going after these tiny little chicken-sized or turkey-sized dinosaurs.”

Zelenitsky speculates that, like birds and crocodiles—closely related animals that share a common ancestor with dinosaurs—Gorgosaurus may have had a two-part stomach. The positioning of the two Citipes, she notes, strongly suggests this possibility, with the legs of the first meal showing more “chemical digestion,” and the legs of the last meal showing more “mechanical digestion or breakdown.”

This discovery also helps support what some paleontologists believe is the key to tyrannosaur evolutionary success: their ability to occupy different ecological niches throughout their lifetime. One paleontological mystery centers around a striking shift in Cretaceous ecosystems. Where once there were a variety of carnivore sizes and species, by the end of the Cretaceous in Asia and North America, there were only two types: massive tyrannosaurs and much smaller dromaeosaurs (feathered theropods such as those of the genus Velociraptor)—and “nothing in between,” Therrien says.

It has been hypothesized that tyrannosaurs were able to occupy all of the ecological niches once held by former midsize and large carnivores over the course of their development: the tyrannosaurs ate smaller prey when they were younger and moved on to megaherbivores as adults. Therrien says they were probably so successful as a species because “they had evolved the ability to occupy all those ecological niches during their own lifespan.”

Zanno, however, disagrees. “To my mind,” she says, “shifting prey preference would have been too widespread among dinosaurian predators to fully explain these phenomena. The dominance of tyrannosaurs in Late Cretaceous ecosystems is a complex story we have yet to tease apart, but I know for certain it’s a problem we will happily continue to tackle in the years to come.”

One thing seems certain: the discovery of this tyrannosaur offers astounding insight into at least one animal. “[Although] unfortunate for the juvenile tyrannosaur,” Zelenitsky says, “it’s lucky for us that it died when it did after eating those meals. Let’s hope more [will be] found!”