The world feels like it’s being set alight; wildfires in Canada and Europe, floods in China, and a never-ending stream of recording-breaking heat waves have garnered numerous headlines.

The feeling that time is quickly running out is very real. And it’s easy to believe that the world cannot tackle big environmental problems. This sense of helplessness is something that I have personally battled for more than a decade. But that feeling is a barrier to action: Nothing has changed when we’ve called for action before, so why should we expect any different this time?

But our past efforts tell us there is hope. The world has solved large environmental problems that seemed unsurmountable at the time. In my role at Our World in Data, I’ve spent years looking at how these problems have evolved, and I think that it’s worth studying these issues, not only for hope, but to understand what went right and what can help us face today’s crises. An eye-opening example is acid rain; studying how the world tackled this geopolitically divisive problem can give us some insights into how we can tackle climate change today.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

It has mostly slipped from the public conversation, but acid rain was the leading environmental problem of the 1990s. At one point, it wasone of the biggest bilateral diplomatic issues between the United States and Canada.

Acid rain—precipitation with high levels of sulfuric or nitric acids—is mostly caused by sulfur dioxide, a gas that is produced when we burn coal. It had severe effects on ecosystems. It dissolved old sculptures, stripped forests of their leaves, leached soils of their nutrients, and polluted rivers and lakes. Emissions from the U.K. would blow over to Sweden and Norway; emissions from the U.S. would blow over to Canada. Just like climate change, it crossed borders, and no country could solve it on its own.

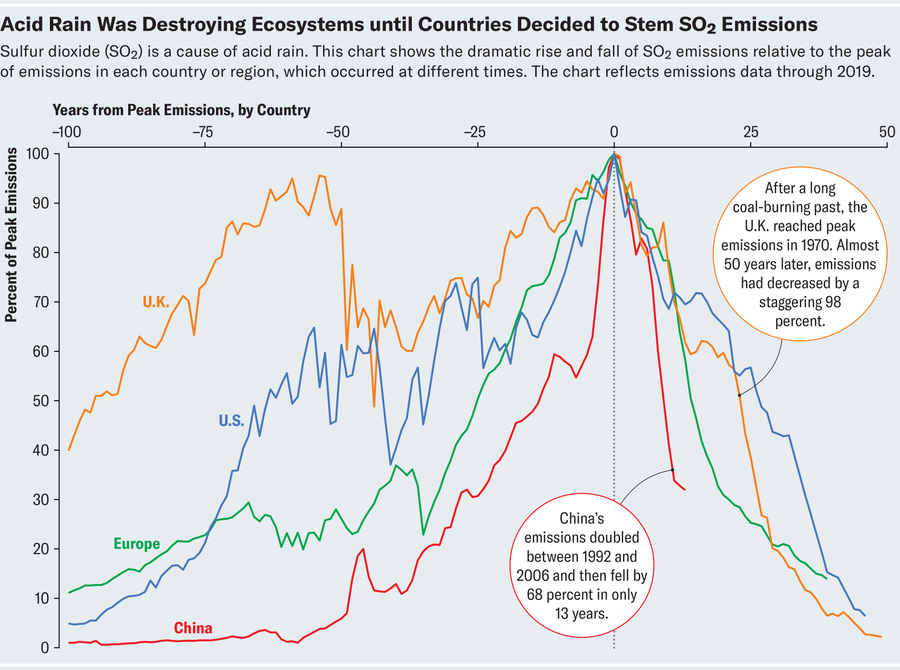

This is a classic game theory problem; outcomes don’t only depend on the actions of one country but on the actions of the others too. Countries will only act if they know that others are willing to do the same. This time, they did act collectively. Government officials signed international agreements, placed emissions limits on power plants and started to reduce coal burning. Interventions were incredibly effective. In Europe, sulfur dioxide emissions fell by 84 percent and in the U.S. by 90 percent. Some countries have reduced them by more than 98 percent.

We did something similar with the ozone layer. The ozone hole was a big coordination problem. No single country was responsible for the world’s emissions of ozone-depleting substances. So there was little upside and some downside to countries taking the lead on their own. They would spend money and implement unpopular environmental policies without making much of a dent in the global problem. The only way to cut emissions substantially was for many countries to join in. It relied on international collaboration. Yet the world solved it. After countries signed the Montreal Protocol, emissions of ozone-depleting substances fell by more than 99 percent.

Credit: John Knight; Source: Data Explorer: Air Pollution, Our World in Data

What we learned from tackling acid rain and the ozone hole can be applied to tackling climate change overall.

First, the cost of technology really matters. The cost-benefit ratio of desulfurization technologies was key to solving acid rain. The cost of installing scrubbers was significant but not budget-breaking. If they had come at a huge cost, countries wouldn’t have made the switch.

Similarly, cheap low-carbon technologies are essential for climate change. Low-carbon technologies used to be expensive, but in the last decade the price of solar energy has fallen by more than 90 percent . The price of wind energy by more than 70 percent. Battery costs have tumbled by 98 percent since 1990, bringing the cost of electric cars down with them. Globally, one in every seven new cars sold is electric. In Europe, one in every five, and in China one in every three.

At the same time, countries are waking up to the potential costs of not moving to clean energy, whether in the form of climate damages—at home or overseas—or being tied to volatile fossil fuel markets.

Second, climate agreements and targets take time to evolve. Negotiations are long. The ozone hole and acid rain were not fixed with the first international agreements on the table. The initial targets were too modest to make a large enough difference. But over time, countries increased their ambitions, amended their agreements and reached for those higher goals.

This is a basic principle of the Paris climate agreement. Countries agreed to step up their commitments to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees Celsius or 2 degrees C. While this has been happening, it definitely hasn’t happened fast enough. The world is on track for an increase of around 2.6 degrees C by 2100. That’s extremely bad. But it’s still a degree lower than where we were heading in 2016. Governments have increased action and increased their target numbers too. And just like with acid rain or the ozone hole, they need to keep aiming higher. If every country fulfilled its pledges, the world would keep temperature rise to 2 degrees C. If they met their net-zero commitments on time, we could sneak below it.

Finally, the stance of elected officials matters more than their party affiliation. Environmental issues do not have to be so politically divisive. Acid rain was a bipartisan divide in the U.S. under Ronald Reagan’s presidency. But it wasn’t a Democrat who finally took action; it was his Republican successor, George H.W. Bush. Before taking office, Bush pledged to be the “environmental president,” a bold stance for many right-wing leaders today, but one that we need to see repeated if we are going to make and reach these loftier goals. In the U.K., there is strong public support for net-zero emissions even among the political right. Margaret Thatcher—arguably one of the U.K.’s most right-wing leaders ever—was one of the earliest to take climate change seriously.

Former German chancellor Angela Merkel is a modern example of a pro-climate conservative leader. A scientist by training, Merkel always acknowledged the threats of climate change, gaining the title of “climate chancellor.” In the late 1990s she led the first U.N. climate conferences and the Kyoto Protocol. In 2007, she convinced G8 leaders to set binding emission reduction targets. It's wrong to frame environmental problems as right-left wing issues. If we’re going to tackle climate change, we need to overcome this divide.

Climate change is not the perfect parallel for the environmental problems we’ve solved before. It will be harder; we should be honest about that. It means rebuilding the energy, transport and food systems that underpin the modern world. It will involve every country, and almost every sector. But change is happening, even if it doesn’t hit the headlines. To accelerate action, we need to have the expectation that things can move faster. That’s where past lessons come in; we should use them to understand that these expectations are not unrealistic. Change can happen quickly, but not on its own; we need to be the ones to drive it.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.

A version of this article with the title “What We Learned from Acid Rain" was adapted for inclusion in the January 2024 issue of Scientific American.